Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson's comments during Supreme Court arguments have raised eyebrows about the potential instability of the Chevron doctrine, a controversial element of administrative law governing judicial deference to agency interpretations.

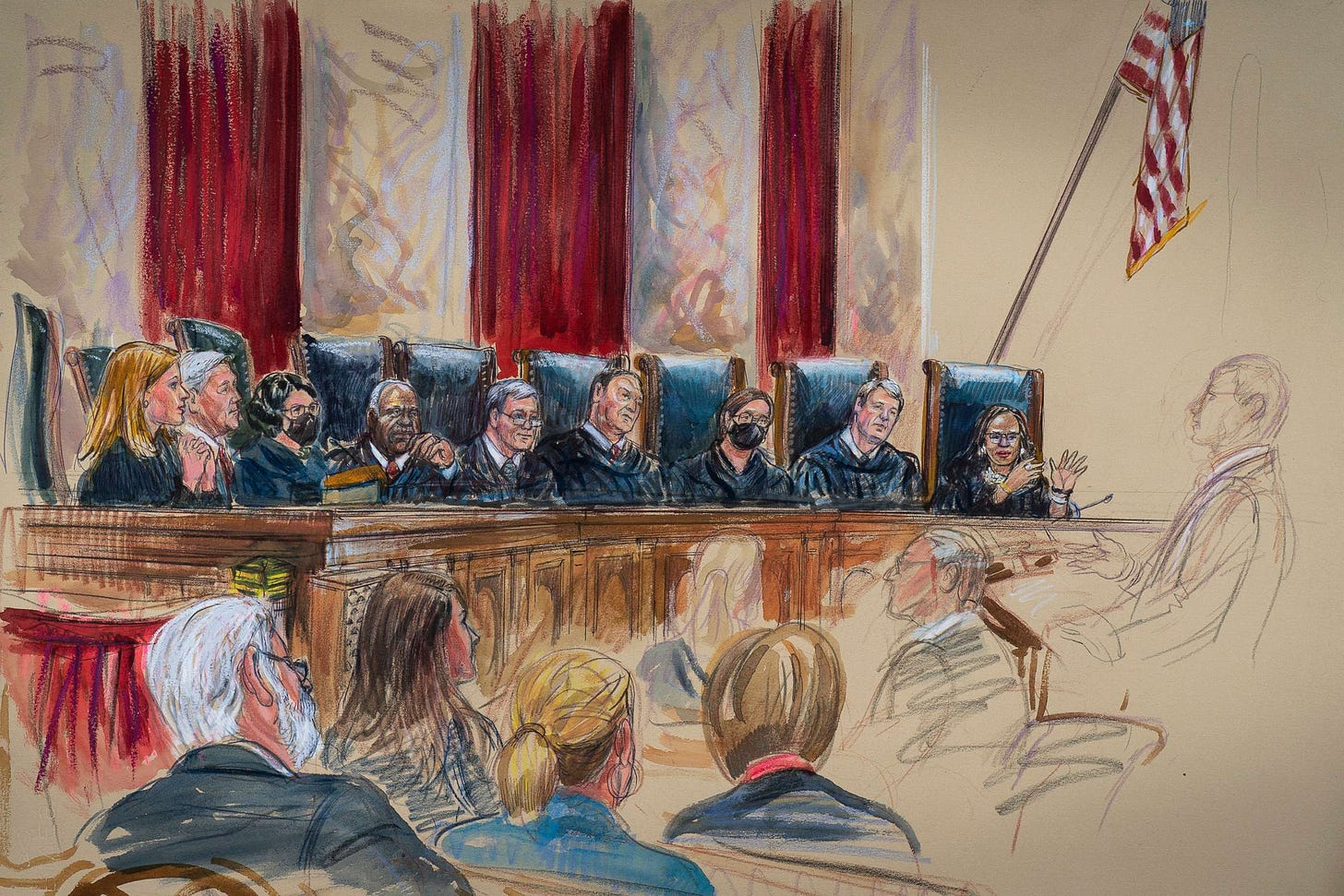

These remarks were particularly highlighted during the oral argument in Corner Post, Inc. v. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, where Justice Jackson's use of the past tense in referring to the Chevron doctrine sparked speculation about its future validity. Jackson's inquiry:

"Is —is that possible because we had other doctrines that prevented, so, you know, for example, Chevron existed and so there were lots of things that already –you know, right? Like, there are reasons why you might not have an uptick,"

suggests a hypothetical landscape where Chevron's guiding principles may no longer be in effect.

This speculation was furthered by Justice Elena Kagan's subsequent questioning, which, while aiming to clarify, seemingly back-peddaled Brow-Jackson’s potential slip:

"There is obviously another big challenge to the way courts review agency action before this Court. Has the –has the Justice Department and the agencies considered whether there is any interaction between these two challenges? And, again, you know, if Chevron were reinforced, were affirmed. If Chevron were reversed, how does that affect what you're talking about here?"

What is Chevron?

The Chevron doctrine, established by the U.S. Supreme Court in Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984), articulates a principle of administrative law that governs the review of federal agencies' interpretation of statutes that they administer. Under this doctrine, courts must defer to agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes if the interpretation is reasonable. The rationale behind Chevron deference is grounded in the expertise of federal agencies in their respective domains and the accountability of these agencies through the political process.

The Chevron doctrine is applied in a two-step process. At the first step, a court must determine whether the statute in question is clear regarding the issue at hand. If the statute is clear, the court must give effect to the unambiguously expressed intent of Congress. However, if the statute is ambiguous or silent on the specific issue, the court proceeds to the second step, which involves assessing whether the agency's interpretation is based on a permissible construction of the statute. If the agency's interpretation is deemed reasonable, the court defers to the agency, even if the court might have reached a different interpretation independently.

This deference to agency interpretations can also diminish the judiciary's role in checking the executive branch, as courts are instructed to rely on agency expertise rather than conduct a thorough review of the statutory interpretation themselves. This arguably undermines the separation of powers by effectively merging legislative and executive functions within agencies, allowing them to draft, enforce, and interpret laws. Moreover, the evolving priorities of different administrations can lead to inconsistent and politically motivated regulatory actions, further complicating the regulatory landscape and affecting the predictability and stability of the law.

Two Challenges This Term

The Supreme Court's review of the Chevron doctrine arises from two related cases concerning a rule issued by the National Marine Fisheries Service that mandates the herring industry bear the costs of observers on fishing boats. This rule was upheld by both the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit, applying Chevron deference to deem the rule a reasonable interpretation of federal law. The challenge to Chevron presented by these cases encapsulates broader legal and constitutional issues, including the scope of judicial review and the separation of powers among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches.

Critics of the Chevron doctrine, represented by the fishing industry, argue that it infringes on the judiciary's role in defining the law by mandating deference to agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes, potentially leading to executive overreach and inconsistent regulatory outcomes. They contend that this undermines the principle of legal certainty and burdens entities, especially small businesses, which may be adversely affected by regulatory changes that result from such deference.

Defenders of Chevron, including the Biden administration and several justices of the Supreme Court's liberal wing, assert the doctrine's importance in allowing agencies to utilize their expertise in filling gaps and defining terms in statutes, which Congress, due to its generalist nature, might not be able to foresee or articulate with precision. This argument suggests that Chevron fosters a division of labor that is both practical and aligned with the intent of Congress, enabling agencies to make policy decisions within the framework of broad legislative directives.

Critics within the Court, including Justices Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, highlight the potential for Chevron to result in policy swings and regulatory uncertainty with changes in administration, arguing for a reevaluation or limitation of the doctrine to preserve the judiciary's role in statutory interpretation.

The discourse among the justices, particularly those skeptical of Chevron, reflects a readiness to reevaluate the doctrine's premise and application, suggesting a judicial inclination towards recalibrating or possibly dismantling the framework established nearly four decades ago. This judicial skepticism, combined with the articulated concerns regarding the doctrine's impact on legal predictability and the separation of powers, suggests a likely pathway to Chevron's reconsideration or revocation by the Court.